Introduction

There is a need for a broad revival in the study of the Gospels. Such a revival can only occur with the revitalization of Synoptic criticism. At the center of this is the Synoptic Problem, which is knowing the correct literary relationship and sequence of the first three Gospels, which are called “Synoptic” because they all exhibit numerous parallels with each other. The evidence in this on this site poses a major challenge to the popular view of Markan (also spelled Marcan) priority, which suggests that Mark’s Gospel was written first and served as a source for Matthew and Luke.

The unfortunate reality is that ideas that are grossly false can gain acceptance and credibility in the highest circles of influence under the guise of being the assured results of scholarship. Criticism itself cannot be solely responsible for the false consensus that developed regarding the priority of Mark. Rather, a consensus can form despite the best scholarship and for reasons beyond its control. Criticism is necessary to expose the fallacies inherent in prevailing theories regarding the Synoptic Problem.

In summarizing the emergence of Markan Priority view, along with refuting the primary arguments for it, repeated reference will be made to William R. Framer’s book The Synoptic Problem, published in 1964. The first half of the book surveys the modern era of textual criticism up to the point of Markan Priority “consensus” which includes a critical review of the primary arguments that were popularized by B.H. Streeter and others.

Farmer provides some context for the genesis of the book in the preface:

The genesis of this book can be traced to the determination to understand how it could be that I once stood before my students and assured them in good conscience that Mark was the earliest Gospel. It was not because of the arguments I then adduced in class. In fact, I distinctly recall feeling that there was a subtlety to the argument from order for Marcan priority which I had never mastered. But the thought never crossed my mind that the argument was itself inconclusive. I used the argument without fully understanding it because it was an unquestioned part of an unquestioned tradition… How had my teachers come to pass on to me the view that Mark was the earliest Gospel? This question led me back to investigate the history of the synoptic problem. (William R. Framer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), pp.vii-viii)

Early Modern Textual Criticism and the Ur-Gospel

Modern textual criticism began in Germany in the 19th century and was aimed at solutions to the Synoptic Problem. However, further developments regarding the analysis of Matthew at that time had significant implications for the understanding of Christian origins among historians and theologians who had the disposition to believe that Matthew was written first. Specifically, the denial of Matthew’s status as an eyewitness Gospel had serious consequences. Although scholars such as Eichhorn and Schleiermacher had previously hinted at this, it was not until Sieffert’s work in 1832 that the matter was decisively settled on critical grounds. Sieffert’s research provided conclusive evidence that Matthew was written after the eyewitness period, which had profound implications for the understanding of the Gospel’s historical reliability. (Farmer, p. 18)

In the 19th century, scholarship on the historical foundations of the Christian faith was of significant dogmatic interest. This was due to the fact that public trust in the reliability of the Gospels as a historical source had been severely undermined, posing a challenge to Christian institutions.

It is during this period that theories of an Ur-Gospel began to be postulated and appealed to by scholars. The “Ur-gospel” (German for “original gospel”) is a hypothetical, reconstructed gospel that was conceived to be the earliest form of the Christian Gospel. It was postulated to have been a collection of the sayings and teachings of Jesus, which was later used as a source for the canonical Gospels of Matthew and Luke. The Ur-gospel is not a physical document, but rather a theoretical construct based on the similarities between the sayings and teachings of Jesus found in the canonical Gospels. This theory of the “Ur-gospel” is a precursor to the later development of the two-source hypothesis and speculations about “Q”, a hypothetical written source that modern scholarship affirms was used by the authors of Matthew and Luke.

During a time of doctrinal crisis, the theory of an Ur-gospel was a welcome and useful contribution. With the recognition that Matthew was written after the eyewitness period, the Ur-gospel hypothesis became an effective tool for serving the dogmatic interests of Christianity in a new way. Once Matthew was dated after the eyewitness period, Scholars who held to a Matthean priority position had no reliable point of contact with the historical foundations of Christianity. At this crisis point in Christianity’s history, the Ur-gospel theory facilitated a framework in which liberal theologians could be critical of the canonical gospels yet while allowing Christianity to maintain its claim to true historical tradition.

The hypothetical Ur-gospel served as a solution that could be appealed to as being from the eye-witness period. Thus, Scholars could reconstruct this apostolic source from Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In this way, they had access to what they regarded as reliable historical testimony concerning the origins of Christianity. The dogmatically motivated need was facilitated by the ability to reconstruct a hypothetical gospel from the canonical gospels that were often viewed as having been dated very late by liberal scholars. The Ur-gospel served a mediating purpose between conservatives and those engaged in textual criticism. In this day and age, Markan Priority combined with the Q hypothesis serves a similar purpose.

The Emergence of Markan Priority

The development of the two-document hypothesis was influenced by two creative ideas: the hypothetical Ur-gospel and the hypothetical collection of sayings (Q). Scholars had considered the idea of an Ur-gospel for over fifty years but did not agree that Mark was the earliest Gospel according to this hypothesis. This was because Mark did not contain many of Jesus’ sayings that were found in both Matthew and Luke.

Heinrich J. Holtzmann was a renowned scholar who analyzed the “Synoptic tradition” using the two-document hypothesis as his fundamental premise. His work is widely regarded as one of the most comprehensive and thorough studies of its kind in 19th-century literature. Holtzmann successfully synthesized the concept of Markan Priority, which enabled him to create a catalog of source texts that were nearly equivalent in content to those derived from methodologies that presupposed Matthean Priority. By assuming Mark was the historically reliable Gospel, Holtzmann’s analysis was not significantly influenced by its content. The two-document hypothesis gained popularity due to its simplicity and because it provided an analytical basis for making claims about the historical Jesus.

The reconstructed “original texts” comprising two sources were expected to be the basis on which historians and theologians could continue their quest for the historical Jesus. Those who believed Mark was early and historically accurate saw that Holtzmann’s procedure supported their belief, while those who believed it was historically unreliable had to admit that Holtzmann’s use of it made little difference in the final outcome. This is why many liberal theologians accepted Holtzmann’s “Marcan hypothesis” even though there was no strong evidence or argument for the priority of Mark. The idea of having two primitive sources was preferred over one and,this seemingly unremarkable use of Mark was sufficient to satisfy traditionalists.

Holtzmann’s meticulous linguistic analysis and reconstruction of two primitive sources had a profound impact that solidified the two-document hypothesis in the minds of many scholars. As a result, his work created an enduring impression that the hypothesis was firmly grounded on a scientific basis. (Farmer p. 46)

The Markan priority hypothesis served as more than just a theory about the source of the Gospels; it also presented a liberal interpretation of the life of Jesus that excluded conflicting resurrection stories and birth narratives. This interpretation allowed liberal theologians to base their faith on historical evidence and simultaneously launch an attack on two key tenets of nineteenth-century orthodoxy: the virgin birth and the physical resurrection. Although the Markan hypothesis was used to battle Orthodoxy on the right, it also became a critical tool for defending the faith against radical attacks from the left (Farmer, p. 42)

The Legacy of B.H. Streeter

During the nineteenth century, scholars began to advocate for the priority of Mark’s Gospel. Christian Hermann Weiss’s work in 1838 and Heinrich J. Holtzmann’s monumental study in 1863 played a significant role in the creation of the Two-Source Hypothesis. This hypothesis, which became the widely accepted theory, combined the idea of a sayings source that was used by both Matthew and Luke to form their Gospels, with the notion of Mark’s Gospel priority.

In 1924, Burnett H. Streeter presented a comprehensive argument for the Two-Source Hypothesis in his book, The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins, published in eleven “Impressions” (editions) between 1924 and 1964. This became the pivotal work that swayed scholarship toward the modern “consensus” and is considered the classic representation of the prevalent perspective of the last 100 years.

Streeter’s Arguments

Streeter’s main arguments for the Two-Source Hypothesis can be summarized as follows:

- Matthew’s Gospel incorporates around 90+% of Mark’s content, including similar language in the details, while Luke’s Gospel includes 50-60% of Mark’s content. This proportion includes material that is verbatim or nearly identical, as well as passages that are paraphrased or condensed in Luke as compared to Mark.

- In most sections that appear in all three Gospels, the majority of the words found in Mark also occur in Matthew and Luke, either in one or both of the Gospels together.

- The order of Mark’s Gospel is generally consistent with that found in Matthew and Luke. When Matthew deviates from the Markan order, Luke tends to follow the Markan order, and when Luke deviates from the Markan order, Matthew usually follows the Markan order. This consistency in the order of events in the Gospels suggests that the authors had access to a common source or sources, which they used to structure their narratives.

- The primitive character of Mark is shown by the use of phrases likely to cause offense, which are omitted or toned down in the other Gospels, the roughness of style and grammar, and the preservation of Aramaic words. Matthew and Luke contain more conventional grammar and vocabulary in various parallels.

- The way in which Markan and non-Markan material is distributed in Matthew and Luke looks as if each used Markan material exhibited in a single document, and were faced with the problem of combining this with material from other sources. (B. H. Streeter, The Four Gospels (1951), pp 151-152)

Fallacious Arguments

The first three arguments presented by Streeter do not provide conclusive proof that Matthew and Luke used Mark as a source, as they also leave open the possibility that Mark used Matthew and Luke as sources. While the similarities in content, wording, and order suggest that the authors were drawing from a common source, these arguments do not definitively prove the direction of dependence between the Gospels.

On the first three points, scholars have criticized Streeter’s conclusion, which is also known as the “Lachmann fallacy” named after the first scholar who suggested Mark’s priority based on the argument from order. Streeter’s fallacious reasoning based on an argument of order was also exposed by G. M. Styler whose excursus on “The Priority of Mark” was published in 1962.

The argument from the order in favor of Mark is based on the observation that the order of material in Mark is generally the same as the order in Matthew or Luke or both, suggesting that Mark has faithfully preserved the true order of the earlier Gospel which all three Evangelists have copied. However, the same phenomena of agreement and disagreement in order could be explained by any hypothesis which gave Mark some kind of middle position between Matthew and Luke.

For example, if Luke were first, and Mark second, and Matthew third, the phenomena of agreement could be achieved if Matthew sometimes followed Mark where Mark had followed Luke, but always followed Mark where Mark had deviated from Luke. However, this hypothesis requires further explanation as to why Matthew would always follow Mark where Mark had deviated from Luke.

Additionally, the conventional notion that Matthew and Luke independently copied Mark is fraught with a similar difficulty in that it requires further explanation as to why Matthew would never deviate from Mark where Luke had deviated from Mark.

Even the Ur-Marcus hypothesis requires further explanation as to why Mark, working independently of Matthew and Luke, would never deviate from that common order of Ur-Marcus to which Matthew and Luke bear concurrent testimony. The argument from the order fails to be conclusive in determining the sequence of the Synoptic Gospels.

Farmer noted in his review of Streeter:

“Streeter and his contemporaries failed to perceive this fundamental and elemental logical fallacy in their basic argument for the priority of Mark. No review of the history of the Synoptic Problem will be adequate that does not help the critic understand this oversight of an entire generation of New Testament scholars, and that does not explain why conscientious investigators even today are reluctant to entertain seriously the thought that the two-document hypothesis might be less than an assured result of nineteenth-century criticism.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964) pp. 51-52)

Alleged Linguistic Evidence that Mark is Primitive

Streeter’s argument presupposed that Mark’s Greek could be proved to be “crude” and “vulgar” in comparison to that of Matthew or Luke. In making these arguments, he presumed Markan priority rather than doing a truly objective analysis, examining cases where Luke appears more primitive than Mark and other cases where Matthew includes more Aramaic features.

Streeter’s idea originates from Abbott, in his famous article “Gospels” in Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1879 which substantially influenced English critical opinion of this issue. Abbott repeated his views in the 1902 version of Encyclopaedia Biblica and, in both of these influential works, Abbott presented “linguistic” evidence in support of the originality of Mark. Abbott listed nine expressions or words used by Mark, which were expressly forbidden by the grammarian Phrynichus. This improper grammar is not seen to the same extent in Luke and Matthew.

However, eight of these nine examples of bad Greek are exhibited in other New Testament books, including John, the Pauline epistles, and Acts. Moreover, seven of the nine examples are seen in either Matthew or Luke-Acts. The fact is that various Gospel writers on occasion used words condemned by grammarians. At the time of the Attistic grammarians (a group of grammarians and scholars from the 2nd – 4th centuries focused on Greek literature), contemporary writers also used bad grammar. This is why the lists were composed by these purists in the first place. (Farmer, 1964, p.122)

The use of bad grammar in Mark speaks nothing about its date of composition, but rather the eccentric literary style of an author who liked to employ alternative syntax. It is fallacious to postulate a rule of literary criticism by which questions of literary dependence can be settled on the basis of good or bad grammar. This is because there is no correlation between good or bad grammar with the originality of authorship. There are many instances in the history of literature where the original work is a superior literary creation compared to the works dependent upon it.

In his article, Abbott also lists two “barbarisms” found in Mark, including where a word is combined with another word having the improper case or a particular word is used improperly to ask a question. Yet, Abbot acknowledges that both these “idioms are common in the Acta Pilati, and perhaps indicate Latin influence.” The Acta Pilati (also known as the Gospel of Nicodemus or Acts of Pilate) is an apocryphal text that purports to be a record of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus Christ, as well as his descent into Hell and subsequent resurrection. This text, which was widely circulated in the early Christian church and is considered an important work of Christian literature, is believed to have been composed in Greek in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, but later translated into Latin.

These “barbarisms” actually suggest that Mark has affinities with later Apocryphal Gospel literature, both in its bad grammar and in its Latinisms (which some mistake for Aramaic idioms). Most notably, Mark has a significant affinity with the Acta Pilati, which is clearly a later document dependent on the earlier Gospels.

Mark’s writing shows multiple influences from Latin. There were scholars, well-known to Streeter, including C. H. Turner, who were familiar with the topic and were particularly aware of the impact that Latin had on Mark’s Greek usage. In response to the question of Latin influence upon Mark, Turner states, “Whence did Mark derive his occasional use of an order of words so fundamentally alien to the Greek language?” and further continues:

Greek puts the emphatic words in the forefront of the sentence, and the verb therefore cannot be left to the last. Latin, on the other hand, habitually closes the sentence with the verb. The conclusion seems irresistible that … Mark introduces in the Greek of his Gospel a Latinizing order” (C.H. Turner, Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. XXIX, July, 1928, p. 355)

The Historic Present

The historic present is a grammatical term that refers to the use of the present tense to describe events that occurred in the past. The historic present, although a common idiom in Latin, is relatively rare in Greek as in English; But Mark uses it 151 times, while Matthew, a much larger document, only exhibits 78 instances and Luke only 4. Luke testifies against the alteration of tense in all but 4 cases, while Matthew concurs with Luke in lacking the alternation of tense approximately 60 times. (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.120)

Streeter makes the erroneous assumption that Mark’s use of the historical present was an Aramaism rather than a Latinism based on an untested presumption that Mark is primitive and close to the Palestinian origins of the Church. It is problematic for those who hold to Markan priority to acknowledge the Latinisms. Doing so, and still maintaining a view of Markan priority, would force them to imagine that Luke and Matthew were cutting down on Mark’s Latinisms which is less likely if the influence of Latin was already strong in the Church.

Mark’s Gospel frequently employs the historic present tense, which serves the purpose of creating immediacy and vividness in the narrative, as if the events are happening in the present moment. This technique is also utilized to emphasize the importance of particular events or to underscore the emotions and reactions of the characters involved. The use of the historical present is a significant stylistic feature of Mark’s novel-like Gospel, contributing to its compelling and engaging storytelling of Jesus’ life. The widespread use of this technique in Mark is not an indication of a more primitive tradition, but rather a deliberate literary choice made by the author to enhance the narrative’s impact.

Agreements of Luke and Matthew Against Mark

Advocates of Markan priority have a major hurdle to overcome. How to disregard the agreements of Luke and Matthew against Mark, known as Minor Agreements. Streeter writes them off by classifying them into categories including (1) Irrelevant Agreements; (2) Deceptive Agreements; (3) Agreements due to the overlap of Mark and “Q”; and (4) Agreements due to Textual Corruption. This technique allowed Streeter to obscure and dissipate the cumulative effect, in the mind of the reader, of the magnitude of agreements that Luke and Matthew share against Mark. The arrangement and procedures that Streeter employed were deceptive and misleading.

In the section on Irrelevant Agreements, Streeter commits a logical fallacy known as begging the question. His argument assumes the priority of Mark, which he believes is established by his five arguments in favor of Markan priority.

Streeter’s Claim of Deceptive Agreements

Streeter categorized a number of agreements of Luke and Matthew against Mark, as “Deceptive Agreements.” He attempted to dismiss this category of agreements based on the idea that two editors working independently on the same text would make the same improvements in various places.

A principal example that Streeter uses is a Greek word φερειν, meaning to carry something, as in an object that one lifts. Streeter claimed it was linguistically inadmissible for this word to be applied to a person or an animal, yet Mark uses it four times as applied to animals or persons. Luke and Matthew use the more fitting word αγειν in places where they parallel Mark. Thus, Streeter claimed that Luke and Matthew are both making obvious corrections.

Although this may seem plausible on the surface, it is more probable that the word choice in Mark reflects the influence of Hellenistic Greek. During this period, the language was evolving, and the vocabulary and grammar used in Mark may have been gradually supplanting the more classical style found in Luke.

It is not true that neither Luke nor Matthew could tolerate Mark’s usage of the less conventional use of a Greek word φερειν meaning to “lead” or “bring” in reference to animals or persons. Although Luke may have preferred the use of αγειν, Luke uses φερειν in other contexts, such as Luke 15:23. This indicates that Luke was perfectly capable of copying the word φερειν if he found it in his source.

Thus, there is no support for Streeter’s notion that Luke would have consistently introduced some form of αγειν in place of φερειν in passages that parallel Mark. The author of Mark seems to have developed a preference for using the term “φερειν” in ten different instances where “αγειν” would have been a suitable alternative. This pattern suggests that “φερειν” became a stereotypical expression used by the author. This observation is consistent with the author’s tendency to incorporate less conventional language in a more innovative narrative. Mark’s Greek exhibits the later tendencies in Hellenistic Greek to a greater extent than either Luke or Matthew. (Farmer, p. 129)

Streeter claimed that other words in Mark would be obvious for both Luke and Matthew to correct. However, these very words are actually not words that either author would be compelled to change if writing after Mark. What Streeter claimed are vulgarisms are words found in both John and Acts, the Greek historian Plutarch (ANT. 33), and the Lxx.

In another case, the word κεντυριων used by Mark is a loan word in Greek taken over from the Latin centurio, a word that is found in the apocryphal Gospel of Peter. Here again, Mark shows more affinity with later apocryphal works under a heaver Latin influence than a primitive Gospel tradition. In reference to several cases observed, Farmer makes the following statement.

“Mark’s Greek seems to reflect certain features of later Hellenistic Greek usage at points where the Greek of Matthew and Luke do not, and that Mark at this point shared this characteristic with second-century Greek literature in general, and with Latinized Hellenistic Greek literature in particular, and interestingly enough with second century Apocryphal Gospel literature.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.130)

A Parallel Example of Alleged Deceptive Agreement

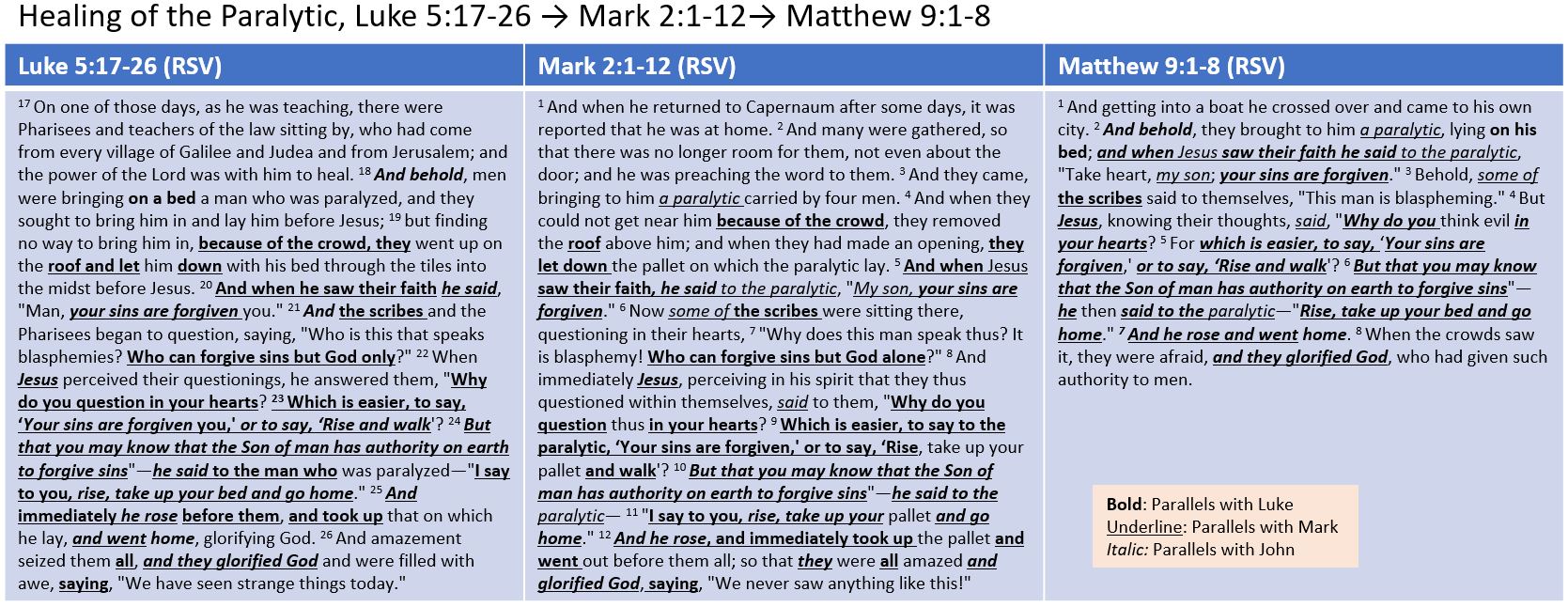

The parallel case of Mark 2:1-12, Matthew 9:1-8 and Luke 5:17-26, regarding the healing of the Paralytic, is an example of what Streeter refers to as a case of Deceptive Agreement. Below is a parallel table of the RSV translation with bold, underline, and italic formatting used to show common words shared between parallels.

In this parallel, multiple elements of agreement are observed between Luke and Matthew not exhibited in Mark. These include:

- Matthew 9:7 and Luke 5:25 exhibits a match of five consecutive words (ἀπῆλθεν εἰς τὸν οἶκον αὐτοῦ) in reference to the Paralytic going to his home, not exhibited in the parallel in Mark. Streeter explains this away as merely an example of deceptive agreement. However, it is most improbable that Matthew and Luke composed the identical five-word sequence independently of each other while also revising Mark. This is especially true because this five-word agreement does not occur in isolation with other minor agreements of Matthew and Luke against Mark, but rather, as Framer puts it, “is but part of an extensive web of interrelated minor agreements, each of which when considered by itself might appear dismissible as insignificant, but when considered together constitute such a concatenation of agreements of Matthew and Luke against Mark as to seem unlikely to be merely accidental, but rather point to some kind of literary relationship between Matthew and Luke.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.132)

- The Semitic term “Behold” (ἰδοὺ) is exhibited in Luke and Matthew but absent from Mark. Streeter relegated “Behold” to his first category as being an “Irrelevant Agreement” stating “Mark, for some reason or other, never uses this word in narrative; Matthew uses it 33 times, Luke 16. No explanation, then is required for the fact that 5 times they concur in introducing it in the same context.” This is clearly an inadequate explanation on Streeter’s part, especially considering his theory is that Matthew and Luke took measures to make the Semitic style of Mark more idiomatically Greek.

- “On a bed” is consistent between Luke 5:18 and Matthew 9:1. Mark has no initial equivalent of “on a bed,” but later makes reference to a pallet in Mark 2:4. There is no apparent reason why both Matthew and Luke independently introduce the particular expression “on a bed” considering the Markan hypothesis of postulates that Matthew and Luke tend to condense Mark.

- “Authority on the earth to forgive sins” (ἐξουσίαν ἔχει ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας) is consistent between Luke 5:24 and Matthew 9:6 in contrast to Mark 2:10 (ἐξουσίαν ἔχει … ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς) exhibiting a different word order, Although this isn’t so clear by reading the English translation, The word order shared between Luke and Matthew is much distinguished from Mark.

- Mark exhibits the historical present “he says” where Luke and Matthew are in agreement with “he said.” This is an agreement that Streeter considered irrelevant. We do see the historical present as a favorite stylistic peculiarity of Mark (151 times) and John (162 times). However, there is no reason to believe that Luke or Matthew would substitute “he said” for “he says” considering that there are numerous instances where they use the historical present in other passages. Matthew used the word in the same form he says (λεγει) 50 times elsewhere in his Gospel. It is unlikely that the author of Matthew would correct a widely used “colloquialism” in Mark 20 times that he uses elsewhere twice as often. Moreover, Luke uses the historic present 13 times in Acts and in 6 instances characterized as Lukan special material (Luke 7:40, 13:8, 16:7, 23, 29, 19:22). There is even a parallel between Mark 5:35 and Luke 8:49 in which the historical present is shared. Thus, there is no basis for presuming that Luke would avoid the historic present when he found it in his source.

- Additionally, there are several examples of agreement of omission of Luke and Matthew against Mark. The most notable is the absence of “carried by four men” exhibited in Mark 2:3 and the absence “take up your pallet” in the quotation of Jesus of Mark 2:9. If Mark was a primitive source for both Luke and Matthew, it is unlikely that they would both omit significant details such as this. This parallel is also a case where Luke’s account is not significantly condensed as compared to Mark. Thus, there is no basis for thinking that Luke made these omissions in an attempt to compress Mark.

The parallel review is one in which numerous “minor” agreements occur in a larger, integrated context. Such a review exposes the questionable character of Streeter’s methodological procedure of dividing up the minor agreements into different categories and then focusing on isolated examples of one category at a time. Streeter also failed to observe that agreements in omission are significant when they occur in these cases where they are in connection with more positive agreements. By isolating agreements from one another apart from the fuller context of parallel passages, Streeter’s methodology served to obscure the significance of those agreements of Luke and Matthew against Mark.

Streeter also failed to acknowledge that there is the same kind of agreement in omission elsewhere in passages where no appeal can be made to the idea that Matthew and Luke compressed Mark. This includes ten passages he dismissed under the category of “Deceptive Agreements.”

Another observation to make is the fact that the text of Mark exhibits greater specificity than both Luke and Matthew, including the “carried by four men” and “take up your pallet,” absent from both Luke and Matthew. This and many other examples of Mark being more specific than either Luke or Matthew, don’t bode well for the theory of Markan priority.

Exhibiting a high level of specificity is a known characteristic of later Apocryphal Gospel literature. Various scholars have observed that the character of Mark suggests a later origin, having a greater affinity with second-century literature. Scholars who take “form-criticism” seriously reject that the greater part of Mark exhibits eyewitness character, and maintain the opinion that the Gospel tradition as it developed into the second century tended to become more specific. (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.134)

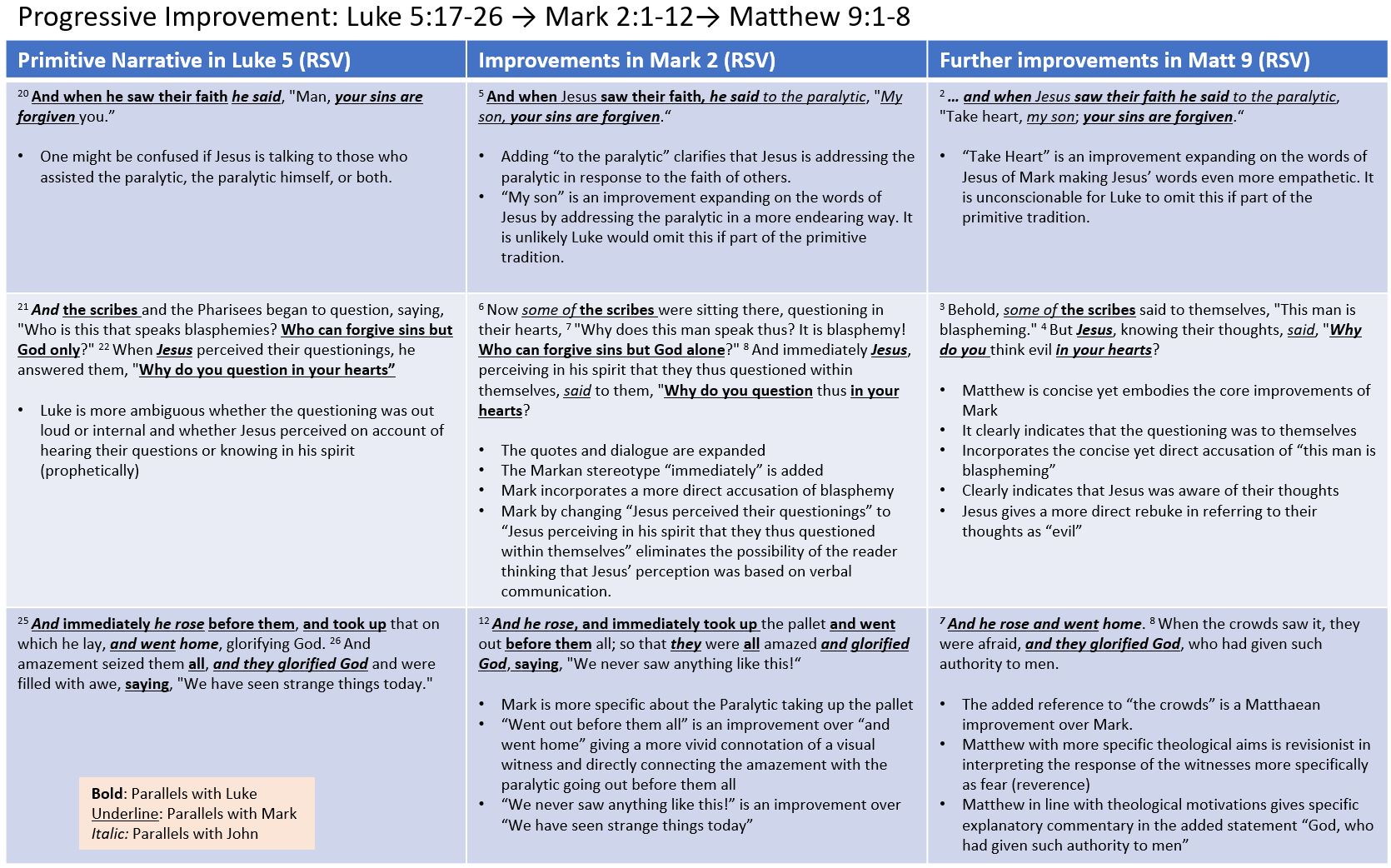

The Same Parallel Indicates Lukan Priority

The article Progressive Embellishment, Luke→Mark→Matthew, explores 36 cases of two stages of progress embellishment from Luke to Mark, and from Mark to Matthew. The parallel of the healing of the Paralytic above could be considered a 37th case. Where Luke is the most primitive and less clear, about particular details, and where Mark makes various improvements, including clarifications and expansion upon dialogue. In these cases, Matthew can be seen to have made further refinements and improvements, resulting in the most developed and polished hybrid text that shares particular agreements with Luke against Mark and with Mark against Luke.

While it is often true that Matthew is more expansive than Mark in parallels shared with Luke and Mark, it is sometimes more condensed. Even when Matthew is compressed, it is often true, as with this example, that Matthew makes notable improvements over Mark. The obvious improvements of Mark and Matthew with respect to Luke are outlined in reference in the table below:

These three examples in the table correspond to the frequent trend observed of progressive embellishment from Luke to Mark, and from Mark to Matthew.

The principal reason that Matthew is more condensed in this case is that the difficulty in reaching Jesus was not likely seen as central to the story. Yet, Matthew makes some allusion to the obstacle that those who brought the paralytic faced in maintaining the identical statement of Mark, “And when Jesus saw their faith he said to the Paralytic.” This implies that the situation presented some type of circumstance in which their faith was demonstrated. Thus, Matthew, although shorter in this parallel, can be clearly assessed as a later development that exhibits clear improvements over Luke and Mark.

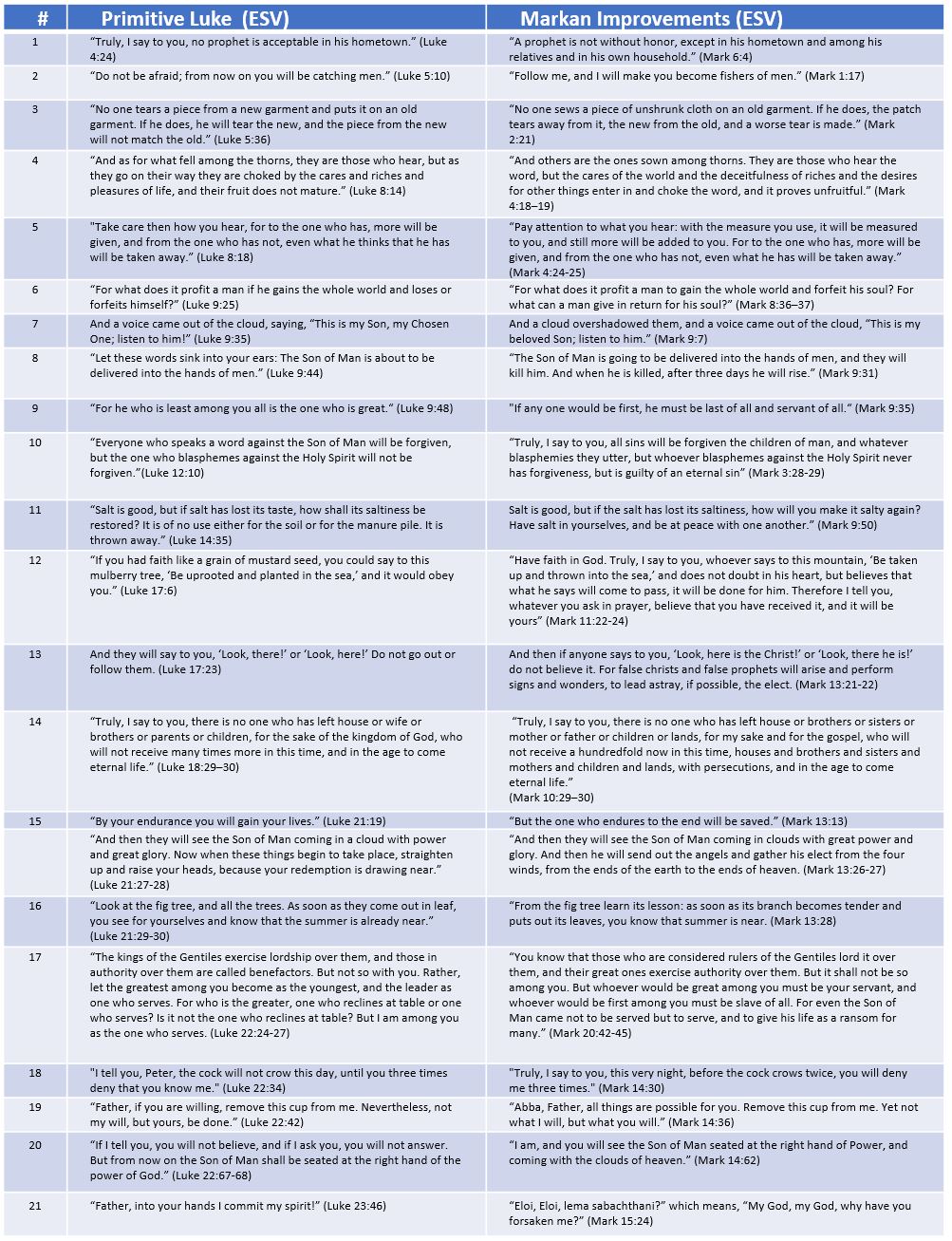

Clear Evidence of the Primitive Tradition

It is commonly believed that the Gospel of Mark contains an earlier and more primitive version of Jesus’ sayings compared to Luke, but this is actually incorrect. In fact, the opposite is true. The table below provides several examples that demonstrate how Jesus’ quotes in Luke are more primitive than the improved versions found in Mark.

Marks use of Aramaic Words

Streeter took another argument from Abbott in affirming the primitivity of Mark. Streeter refers to eight instances in which Mark utilizes Aramaic words. Of these, Luke has none, while Matthew exhibits only one, the name Golgotha.

The focus on the particular Aramaic words gives a false impression that Mark’s text preserves more Aramaisms and Semitisms than Luke and Matthew. The presence of specific Aramaic terms, translated for the readers’ benefit in Mark, obscures the fact that Luke exhibits the text with the greatest concentration of Semitisms (see Validation of Special Luke: Semitisms), and that Matthew also has more Semitisms than Mark.

Especially with respect to Greek stories of healing attributed to Jesus, the presence of foreign Aramaic words can be explained as known contemporary literary practice. When Mark included the meaning of these Aramaic words attributed to Jesus, he implicitly recognized the fact that they would not be understood by many of his intended readers. This suggests they were inserted for literary effect. Farmer noted, “It is well known that in the second century, unintelligible and esoteric words were used for effect in some Christian literature.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.172-173)

Here are a few examples:

- The Apocryphal Acts of Pilate (XI. 1) adds the note “which being interpreted means.” This comes prior to the “into your, hands I commit my Spirit” taken from the Lukan passion narrative.

- Irenaeus protested against those who used “Hebrew” words in the churches “in order,” he writes, “to more toughly to bewilder” the Christian initiates (Irenaeus Against Heresies, Bk. 1, Chapt. 21 Par. 3).

- Jesus’ last words on the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me, according to Mark and Matthew is given by them both in Greek and either Aramaic (Mark) or Hebrew (Matthew). In this context, they both use non-Greek words for dramatic effect at the moment of Jesus’ death.

The use of sacrosanct language in certain contexts may suggest an attempt at manipulation or coercion. Mark likely included Aramaic words and phrases to give his narrative an air of authenticity. The continued practice of incorporating Aramaic or Hebrew words into Christian literature and oral teaching indicates that such usage is no indication of relative dating or order of the Gospels.

In this regard, Farmer states:

“The presence in a Gospel of Aramaic terms which are translated for the reader’s benefit may be due to one or more of several causes. It is known, for example, that foreign words are sometimes introduced into Hellenistic healing stories (Cf. Bultmann). The presence of Aramaic words in the Greek stories of healing attributed to Jesus can be adequately explained by appeal to this known contemporary literary practice. The presence of such terms in a Gospel, therefore, is by no means a guarantee of the primitivity of that Gospel. The fact that Aramaic words were attributed to Jesus in two healing stories in Mark, whereas no such Aramaic expressions occur in the healing stories of Matthew or Luke, is, on form-critical grounds, as well or better explained as a sign of Hellenistic influence on Mark” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.172)

In conclusion, the use of Aramaic words is not a sound basis for arguing the Priority of Mark.

Problematic Verses in Mark Omitted Elsewhere

Abbott, in the 1879 Encyclopedia Britannica “Gospels” article, identified nine passages in Mark that he believed were theologically problematic. These include:

- Mark 6:5, “he could do no mighty work there, except that he laid his hands on a few sick people and healed them.” — This indicates Jesus was limited in power and ability.

- Mark 1:32, 34, “They brought to him all who were sick or oppressed by demons… And he healed many who were sick with various diseases, and cast out many demons” – This indicates many but not all were healed.

- Mark 3:20-21, “And when his family heard it, they went out to seize him, for they were saying, “He is out of his mind.”

- Mark 10:35, “And James and John, the sons of Zebedee, came up to him and said to him”—The petition is attributed to two persons rather than one (as in Matthew).

- Mark 15:44, “Pilate was surprised to hear that he should have already died.” — The implication of a surprisingly quick death has led some to suggest that Jesus didn’t really die at all.

- Mark 3:15, “and have authority to cast out demons”—Mark lacks “and heal diseases” that Matthew exhibits, implying that Jesus gave them more limited power.

- Mark 8:24, “And he looked up and said, “I see people, but they look like trees, walking.” — The miracle was complete instantaneously.

- Mark 11:21, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree that you cursed has withered.” — according to Mark, the withering occurred a day later, not instantly as in Matthew.

- Mark 16:4, “They saw that the stone had been rolled back”—Mark lacks reference to an angel being at the tomb, thus opening up speculation that the body was stolen.

Such expressions Abbott stated were “likely to be stumbling blocks in the way of weak believers so that they are omitted in the later Gospels, and would not have been tolerated except in a Gospel of extreme antiquity.” (p. 802b)

Several of these apply only to Mark in view of Matthew, giving more of an indication of Mark preceding Matthew, but are not nearly as persuasive in demonstrating the priority of Mark over Luke.

Streeeter adopted Abbott’s line of reasoning, which he prefaced as follows:

“in the same spirit [of reverence] certain phrases which may cause offense or suggest difficulties are toned down or excised. Thus, Mark’s “he could do there no might work” (Mark 6:5) becomes in Matthew 13:58 “he did not many might works”; while Luke omits the limitation altogether.” (Streeter, The Four Gospels, p. 162)

In addition to the nine examples from Abbott, Streeter added the example of Mark. 10:18 “Why do you call me good.”

In this case, the text of Luke is identical to that of Mark, indicating that this text caused Luke no offense at all. Although there is reason to believe the particular text in Mark “might cause offense or suggest difficulty” to Matthew, this is not the case with Luke.

The nine examples provided by Abbott, along with the one added by Streeter, are given in support of the claim that Mark predates Matthew due to the primitive nature of Mark’s text presenting challenges. These examples are less persuasive in indicating Markan priority over Luke. This argument ultimately falls short with respect to Luke when critically evaluating the nature of Mark as a derivative literary work.

The close evaluation of Mark results in the realization that Mark is largely an eccentric revision of the primitive Gospel narrative (Luke) along the lines of second-century Apocryphal Gospel literature. Unlike the character of Luke being more of a histography, Mark is more of a novelist who adds increased dramatization, expands on the dialogues, and adds sensational details to embellish the story further. In revising the narrative, Mark substitutes words and uses unconventional grammar to innovate and capture the attention of the reader. Some verses alleged to be problematic are in line with the author’s proclivity to add interesting details and make the narrative more intriguing.

For more on this, see all the other articles pertaining to Mark on this site. The preponderance of the evidence indicates that Mark expanded upon Luke. Approximately 65% of the entire Gospel of Mark are parallels with Luke that expand and embellish the primitive Gospel narrative exhibited by Luke.

Streeter’s acknowledgment of prot0-Lukan Priority

Although Streeter argued for Markan priority, he observed that where there is a parallel between Luke and Mark, Luke often exhibited an earlier tradition. His work-around was to speculate about a proto-Luke that predates Mark, but that also derives from a Q source. In doing so, Streeter actually advocated proto-Lukan priority, while simultaneously arguing for Markan priority. Under the theory that Luke’s Gospel is based on “Proto-Luke” itself, he stated additional rationale for the theory:

A further reason for supposing that Luke found the Q and the L elements in the non-Marcan sections already combined into a single written source [Proto-Luke] is to be derived from a consideration of the way in which he deals with incidents or sayings in Mark, which he rejects in favor of other versions contained either in the Q or the L elements of that source. (B. H. Streeter, The Four Gospels (1925), p. 209)

In summing up his observations on how Luke apparently deals with Mark. Streeter states the following:

It would look, then, as if Luke tends to prefer the non-Marcan to the Marcan version, and this is whether it be the longer or the shorter, and whether it belongs to that element in the source which we can further analyze as being ultimately derived from Q or from the element which we call L. But such a preference, especially where it is a preference in regard to the order of events, is much more explicable if Q and L were already combined into a single document. For the two combined together would make a book distinctly longer than Mark, and would form a complete Gospel. Such a work might well seem to Luke a more important and valuable authority than Mark. But this would not be true of either or L in separation. The Conclusion, then, that Q+L lay before the author of the Third Gospel as a single document [Proto-Luke] and that he regarded this as his principal source appears to be inevitable. (B. H. Streeter, The Four Gospels (1925), pp. 211-12)

Given Streeter’s theory of proto-Luke, he expresses the implication that Luke must have regarded his primary source, a source more primitive than Mark, as superior to Mark.

Post-Streeter Dogmatism

We have reviewed both the historical context and the principal arguments Streeter used in advocating Markan Priority. A critical review gives one the understanding that Markan Priority was accepted with the absence of overwhelming evidence in its favor and despite the many counterindications, including the many agreements of Luke and Matthew against Mark.

In trying to address the related difficulties, Streeter did not conduct an impartial investigation but made an effort to explain away substantive evidence on the basis of a presumption that Mark was original and primitive.

Farmer noted that despite the weakness of Streeter’s reasoning for Markan priority, he expressed a high level of certainty in his statements and was forceful in his attitude. He further ignored the work of significant dissenters and lacked engagement with those who questioned the views he further popularized. The post-Streeter period of Synoptic criticism is characterized by a dominant and dogmatic attitude, distinguishing it from the pre-Steeter period, characterized by a tentative posture assumed by scholars engaged in the field.

Farmer notes:

“This shift in the climate of critical opinion toward an attitude of impatient dogmatism on the question of Marcan priority… would appear … to be a post-war development.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.177)

Accordingly, Markan priority has been the dominant view among scholars since the late 1920s, although, there never was a true consensus.

Farmer’s Critique of “Consensus” Dogma

Concluding the survey of critical scholarship and the history of the development of the consensus view, Farmer sums up the decisive factor as follows:

“The decisive factor in the triumph of the Marcan (or two-document) hypothesis was not any particular scientific argument or series of arguments, however important some of these may have been. The decisive factor in this triumph… was theological.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.57)

Gospel criticism developed under the presuppositions of a hypothetical Ur-Gospel or two-source hypothesis involving Q has proved to be faulty. Farmer notes, “It is based not upon a firm grasp of the primary phenomena of the Gospels themselves, but upon an artificial and deceptive consensus among scholars of different traditions of Gospel criticism” (Farmer, p. 38). A notable scholar is quoted to have said, “I myself am often astonished to see how naturally everything proceeds from an observation which I found I had made, without rightly knowing how I came by it.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.39)

Farmer’s ended his critical review with the assessment that:

“The only sound historical judgment that can be rendered in a critical review of the history of the Synoptic Problem is that “extra-scientific” or “nonscientific” factors exercised a deep influence in the development of a fundamentally misleading and false consensus.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.90)

Streeter’s systematic examination of the minor agreements of Matthew and Luke in contrast to Mark, further strengthened the allure of this academic misconception. This view gained momentum over time as each new generation of diligent scholars built upon the work of their predecessors.

Eventually, a new argument emerged, which although never published, had a more significant influence in reinforcing the belief in the priority of Mark than any previous argument presented by Streeter or anyone else. This argument can be summarized as follows: “It is impossible to imagine that so many scholars could have been incorrect on such a fundamental point for such an extended period.” This argument is potent because it cannot be effectively refuted. Scholars value intellectual humility and genuine piety in their colleagues. Therefore, any critic who challenges a consensus opinion endorsed by a vast majority of experts over an extended period of time risks being viewed as academically arrogant and may lose the respect of their colleagues. (Farmer, p. 195)

However, this argument lacks substance. Its influence in the field of source criticism in Gospel studies is more indicative of the perplexing impasse that has hindered progress since Streeter’s era, rather than its actual validity or worth.

Upon examining the precise settings in which the minor agreements take place within the Gospels, a “literary analysis” of the Evangelist’s vocabulary, grammar, and writing style fails to substantiate the argument put forth by Streeter. The agreements of Luke and Matthew against Mark continue to pose a significant literary quandary for those who maintain that both Matthew and Luke derived their content from Mark. A viable hypothesis must account for this particular phenomenon. This, in addition to the evidence of the primitive nature of Luke, are the major stumbling blocks of the two-source hypothesis.

Where We Are Now

Throughout the early and mid-20th century, there were numerous dissenting scholars, including Chapman, Jameson, Butler, Park, Styler, Farrer, Farmer, and Lindsey. Only a minority of Gospel critics have shown sympathy towards the views of these scholars, who were seen as deviating from the newly established orthodoxy regarding the Synoptic Problem.

Since Streeter, additional scholars have attempted to supplement his arguments on Markan priority and the Gospel of Q Hypothesis. Numerous scholars have also refuted these arguments. The arguments and counterarguments are largely summarized in the work of Arthur J. Bellinzoni, Jr., The Two-Source Hypothesis: A Critical Appraisal, published in 1985.

Some, who have attempted to advance the evidence of Markan priority, have ended up with datasets implying the contrary. For example, in 1959, Mgr De Solages published a statistical study of the Synoptic Gospels, A Greek Synopsis of the Gospels, which spans 1128 pages and aimed mathematically to validate the two-document hypothesis. On the contrary, Framer noted, the data supported indicated Mark being the second of the three gospels, the “middle term”:

“His work is in fact a monument to the mesmerizing power of the two-document consensus. For what Solages has actually done is to document in exhaustive detail the fact that Mark is in some sense the middle term between Matthew and Luke.” (W. R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem (1964), p.197)

The numerous articles on this site demonstrate that Mark is indeed the middle term.

In disagreement with both Streeter (Markan Priority) and Farmer (Matthean Priority), this site demonstrates that the preponderance of the evidence supports the view that Luke is actually the most primitive Synoptic Gospel. The last of the three is Matthew. A sound basis is provided for Lukan Priority and Matthean Posteriority.