Introduction

According to patristic writings and tradition, John came after Luke. The oldest document is the Muratorian fragment, a list of New Testament books, written during the latter half of the second century. It recorded the gospel order of Luke before John. Origen (185-255), on more than one occasion, enumerates an order in which he noted the Gospel “according to John, last of all.” (Eusebius. H.E. VI, 25).

Despite early patristic writings and modern scholarship which has confirmed John was written last, some scholars claim John stems from a tradition that is completely independent of the Synoptic Gospels. Others claim that John is even a more primitive tradition than the Synoptic Gospels, being the earliest Gospel written.

While this notion is refuted by the many scholars who have demonstrated a dependency of John on Mark, this can further be refuted by demonstrating the profound literary relationship and dependency of the Fourth Gospel on Luke.

Although there are not as many verbatim agreements between John and Luke as there are between John and Mark, there is extensive agreement of other sorts. For example:

- Like Luke, John does not explicitly describe Jesus being baptized by John.

- Like Luke, John contains no account of a nighttime trial of Jesus before the Sanhedrin

- Like Luke, John has the risen Jesus appear to his disciples together in Jerusalem

- Like Luke, John portrays Jesus as interested in Samaria and Samaritans

- In many other respects, John shows affinities with Luke not seen in Matthew and Mark.

John A. Bailey, in the book The Traditions Common to the Gospels of Luke and John, conducts an analysis of the material of Luke and John. He examines the cases in which the two gospels agree with each other in ways lacking in Mark and Matthew. These examples indicate that John is in at least some of these places dependent on Luke’s gospel in its present form. Bailey contends that his analysis proves that John drew on Luke and therefore could not have been written earlier than Luke. (John A. Bailey, The Traditions Common to the Gospels of Luke and John. Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1963.)

Other scholars have identified additional parallels and literary relationships between John and Luke. Keith L. Yoder has published three key papers demonstrating John’s literary dependence on Luke.

- From Luke to John, Lazarus, Mary, and Martha in the Fourth Gospel: Keith Yoder examines John’s Raising of Lazarus and Anointing of Jesus texts and explores literary parallels with Luke’s Lazarus and Mary/Martha texts. He shows that there is a significant and orderly array of such parallels between the Luke and John texts, constituting strong evidence of inter-textual influence between Luke and John. He then shows that this relationship is literary rather than oral and that the literary dependence flows from Luke to John.

- Keith L. Yoder. “From Luke to John: Lazarus, Mary, and Martha in the Fourth Gospel” Eastern Great Lakes Biblical Society 2011 Annual Meeting

- PDF Download Available at:http://works.bepress.com/klyoder/4/

- Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John: The Foot Washing of John 13:1–17 is a literary composition, as a creative imitation of the Foot Washing and Anointing of Luke 7:36–50. Comparison of the respective settings, action descriptions, dialogs, and transitions brings to light a large array of mostly unexplored literary connections between these two texts. Analysis of the parallel features reveals a high level of density, order, and distinctiveness that clearly establishes an intertextual relationship of creative imitation. Key markers of directionality arising from the evidence points to Luke’s text as the original and John’s as the mimesis.

- Keith L. Yoder. “Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John” Ephemerides Theologicae Lovaniensis Vol. 92 Iss. 4 (2016) p. 655 – 670 ISSN: 0013-9513

- PDF Download Available at: https://works.bepress.com/klyoder/25/download/

- One and the Same? Lazarus in Luke and John: The Lazarus of Luke 16 and the Lazarus of John 11-12 are largely one and the same. Yoder addresses such questions as (1) When was the story composed relative to the contiguous text? (2) How is it interwoven with the rest of John? (3) Whence came this otherwise unknown brother of Mary and Martha? (4) Why is his story here at this turn in the Fourth Gospel? The interpretation of John’s Lazarus narrative has languished in virtual stalemate for some time. Yoder brings new evidence to the table, to gain a fresh perspective on the composition of that story and its relationship to Luke 16, in the context of a carefully constructed array of network connections with earlier and later texts in John. Yoder identifies connections between Lazarus and the Temple Cleansing and how they illuminate why John moved his Cleansing from Crucifixion week all the way back to join with Jesus’ first miraculous sign at the wedding.

- Keith L. Yoder. “One and the Same? Lazarus in Luke and John” Novum Testamentum Vol. 64 Iss. 2 (2022) p. 184 – 209 ISSN: 1568-5365

- PDF Download Available at: https://works.bepress.com/klyoder/60/download/

Parallels with a literary relationship between Luke and John:

Below are 18 cases of internal evidence of a literary relationship between John and Luke summarized in this article. Many of these cases further indicate that John incorporates elements from Luke and thus is dependent on Luke and comes after Luke.

- Speculation about John the Baptist, Luke 3:15 → John 1:19, 27

- A Miraculous Catch of Fish, Luke 5:1-2 → John 21:1-14

- The anointing of Jesus and the Mary-Martha Stories, Luke 7:36-39 → Mark 14:3-9 → John 12:1-6

- Foot washing from Luke to John, Luke 7:36-50 → John 13:1-20

- Mary-Marta + Lazarus Stories, Luke 10:38-40, Luke 16:19-31 → John 11:1-45, John 12:1-3

- The Holy Spirit as a Teacher, Luke 12:12 → John 14:26

- Hate, Even Your Own Life, Luke 14:25 → John 12:25

- The Approach to Jerusalem, Luke 19:37-40 → John 12:12-19

- Jesus staying on the Mount of Olives, Luke 21:37-38 → John 8:1-2

- Woman Caught in Adultery, Luke 21:37-38 → John 7:53-8:11

- Satan and Judas, Luke 22:3 →John 13:2, 27

- The Last Supper, Luke 22:14-38 → John 13-17

- From the Last Supper to the Arrest, Luke 22:39-53 → John 18:1-12

- Jesus’ Appearance before the Jewish Authorities, Luke 22:53-71 → John 18:13-28

- The trial before Pilate, Luke 23:1-25 →John 18:29-19:6

- Jesus’ Crucifixion, Death and Burial, Luke 23:25-56 → John 19:17-42

- Resurrection and Post-Resurrection Narratives, Luke 24 → John 20

- Examining of Jesus’ Wounds, Luke 24:37-39 → John 20:24-28

1. Speculation about John the Baptist, Luke 3:15 → John 1:19, 27

The earliest similarity between the two Gospels is found in their accounts of John the Baptist. In Luke’s Gospel (Luke 3:15-16), the people question whether John is the Christ, and John responds by stating that there is one mightier than him, coming after him, whose sandals he is unworthy to untie. In John’s Gospel (John 1:19-27), the Jews send priests and Levites to ask John who he is, and he denies being the Christ but mentions the one coming after him whose sandals he is unworthy to untie. Additionally, in Acts 13:25, during a speech in the synagogue in Antioch, Paul refers to John’s statement about not being worthy to untie the sandals of the coming one. What is unique about John and Luke is the connection between the statement about the coming one and the speculation about John’s identity by the Jews. In Luke’s Gospel, this connection is made by the evangelist himself.

Luke 3:15-16 (RSV)

15 As the people were in expectation, and all men questioned in their hearts concerning John, whether perhaps he were the Christ, 16 John answered them all, “I baptize you with water; but he who is mightier than I is coming, the thong of whose sandals I am not worthy to untie; he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire.

John 1:19, 27 (RSV)

19 And this is the testimony of John, when the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem to ask him, “Who are you?”… 27 even he who comes after me, the thong of whose sandal I am not worthy to untie.”

Acts 13:25 (RSV)

25 And as John was finishing his course, he said, ‘What do you suppose that I am? I am not he. No, but after me one is coming, the sandals of whose feet I am not worthy to untie.’

2. A Miraculous Catch of Fish, Luke 5:1-2 → John 21:1-14

The third and fourth gospels each have narratives about miraculous catches of fish that share certain elements.

Luke 5:1-11 and John 21:1-14 both narrate miraculous catch of fish stories involving Jesus and his disciples. While there are differences between the two accounts, they share some common elements not found in the Gospel of Mark or Matthew:

- Both stories revolve around Jesus directing the disciples to cast their nets for a catch, resulting in a miraculous and abundant haul of fish. While this specific miracle is not mentioned in Mark or Matthew, it is unique to Luke and John.

- Presence of Simon Peter: In both Luke 5:1-11 and John 21:1-14, Simon Peter plays a significant role in the narrative. He is not mentioned in similar stories in Mark or Matthew.

-

Jesus’ interaction with the disciples: In both accounts, Jesus communicates directly with the disciples and provides guidance on where to cast their nets, leading to the miraculous catch.

These common elements suggest a literary relationship between Luke and John for these accounts, and that John adopts the details from Luke’s account’ while changing and expanding the story.

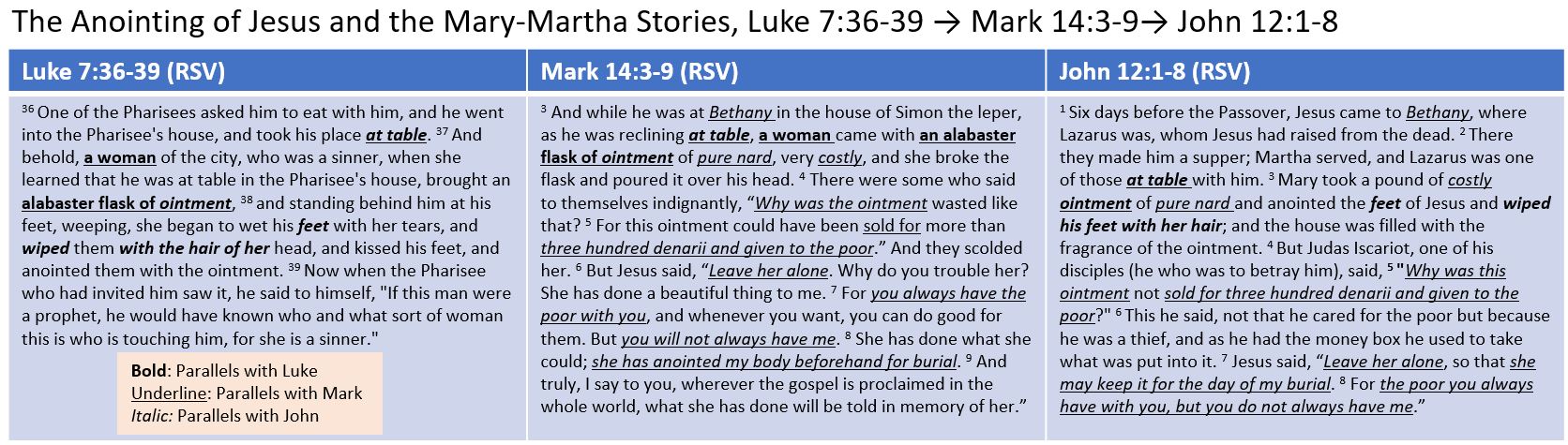

3. The anointing of Jesus and the Mary-Martha Stories, Luke 7:36-39 → Mark 14:3-9 → John 12:1-6

Regarding the account of the anointing of Jesus, there are remarkable similarities between John’s version and the one found in Mark 14:3-9 (which Matthew closely follows): (a) the cost of the ointment being 300 denarii, (b) the incident taking place in Bethany at the beginning of the passion account, (c) the reproach directed towards Jesus for the woman’s extravagance, (d) Jesus’ defense of the woman by making a statement about the poor, (e) the reference to the anointing of Jesus’ body after his death, and (f) the occurrence of the word “nard” (translated from the Greek word “spikenard”), which is not found elsewhere in Greek literature as early as it appears in the New Testament. These similarities, particularly the use of the word “nard,” make it clear that John has taken inspiration from Mark and used Mark’s text directly as a source, with the intention of recording the same event.

John not only heavily relies on Mark’s account but he also incorporates two details from Luke’s story: The stories of Jesus’ feet being anointed by a woman are found in both Luke 7:36-50 and John 12:1-8, with a notable similarity: in both accounts, the woman uses her hair to dry his feet. Additionally, John identifies the woman as Mary and mentions her sister Martha, who is also mentioned in Luke 10:38 as serving while Jesus is a guest. These similarities suggest that John was familiar with Luke’s gospel.

In John 12:1-8, the story of Jesus being anointed by a woman is presented, but the writer assumes that the reader is already familiar with the story as told in Luke 7:37-38, as he identifies Lazarus’ sister Mary as the woman who anointed Jesus. It is notable that the language used in both versions of the story is quite similar. John’s version shows several similarities to Luke’s account that are absent in Mark.

Here is a brief summary of affinities with Luke:

- The verb ἐκμάσσω (“to wipe”) is used only five times in the New Testament, appearing twice in Luke 7 in reference to the repenting woman, twice in John in reference to Mary (both here and in the anointing account in John 12:3), and once in John’s account of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet in 13:5. In his own version of the anointing, the Johannine evangelist shows indebtedness to Luke rather than Mark.

- While Mark and Matthew state that the woman anointed Jesus’ head, in Luke and John she anoints his feet.

- Mark and Matthew both attribute objections to the woman’s actions to multiple unnamed people, whereas Luke and John name the individuals: “The Pharisee who had invited him” (Luke 7:39); “Judas Iscariot… who was about to betray him” (John 12:4).

- Immediately following this story in Luke, the Evangelist names three women, including Mary Magdalene, who “served [διηκόνουν]” Jesus and his disciples (8:2–3). In John’s account, the woman who anointed Jesus is named Mary, while her sister Martha “served [διηκόνει] dinner” (John 12:2; cf. Luke 10:39–42).

Regarding the drying with hair, it doesn’t fit well with John’s narrative. It’s unclear why Mary would wipe off the salve, as the whole point of the anointing was to apply it to the feet. In any case, Mary is not depicted as a repentant sinner in John’s version, which would provide a rationale for using her hair instead of a towel. The difficulties presented can only be explained by the fact that John intentionally and carefully combined the accounts of the anointing as they appear in Mark and Luke’s gospels, even though this combination resulted in a noticeable inconsistency. The evidence suggests that John knew and used Luke’s gospel in its current form. It appears that John combined multiple synoptic traditions, in an unusual way. This is because the author was more reliant on the synoptic gospels regarding the Passion where traditions had already crystallized early on. This dependence on the synoptic gospels was not typical for John earlier in the gospel.

An additional aspect of John’s account in chapter 12:1-8 is worth noting, which is the appearance of the sisters Mary and Martha, as also present in the story of Lazarus’ resurrection in chapter 11. This detail is significant because Luke includes a story in which Martha and Mary are also present, and the context, where Jesus is a guest, is the same as in John 12:1. Although Mary’s actions in Luke 10:38 and John 12:1 are different, both sisters serve in both stories. John’s mention of Martha in verse 2 is extraneous, since the story otherwise only focuses on Mary. This suggests that John added this detail from Luke 10:38 to clarify that the two women in John 11 and 12 were the same as those in Luke’s account. However, this action by John is atypical because he rarely writes his gospel to supplement the synoptic tradition in such a way. John probably included this detail from memory because he considered the Lazarus story (which forms the climax of the first half of his gospel) and the anointing passage (which serves as an introduction to the concluding half of his gospel) to be crucial, and he wanted to highlight their relationship to a tradition that he knew was already widely known in the Church through Luke’s gospel. The view that Luke knew John’s version of the story would be most problematic since it would require a complex history of tradition to explain the similarities between the two accounts, which are absent in Mark’s version.

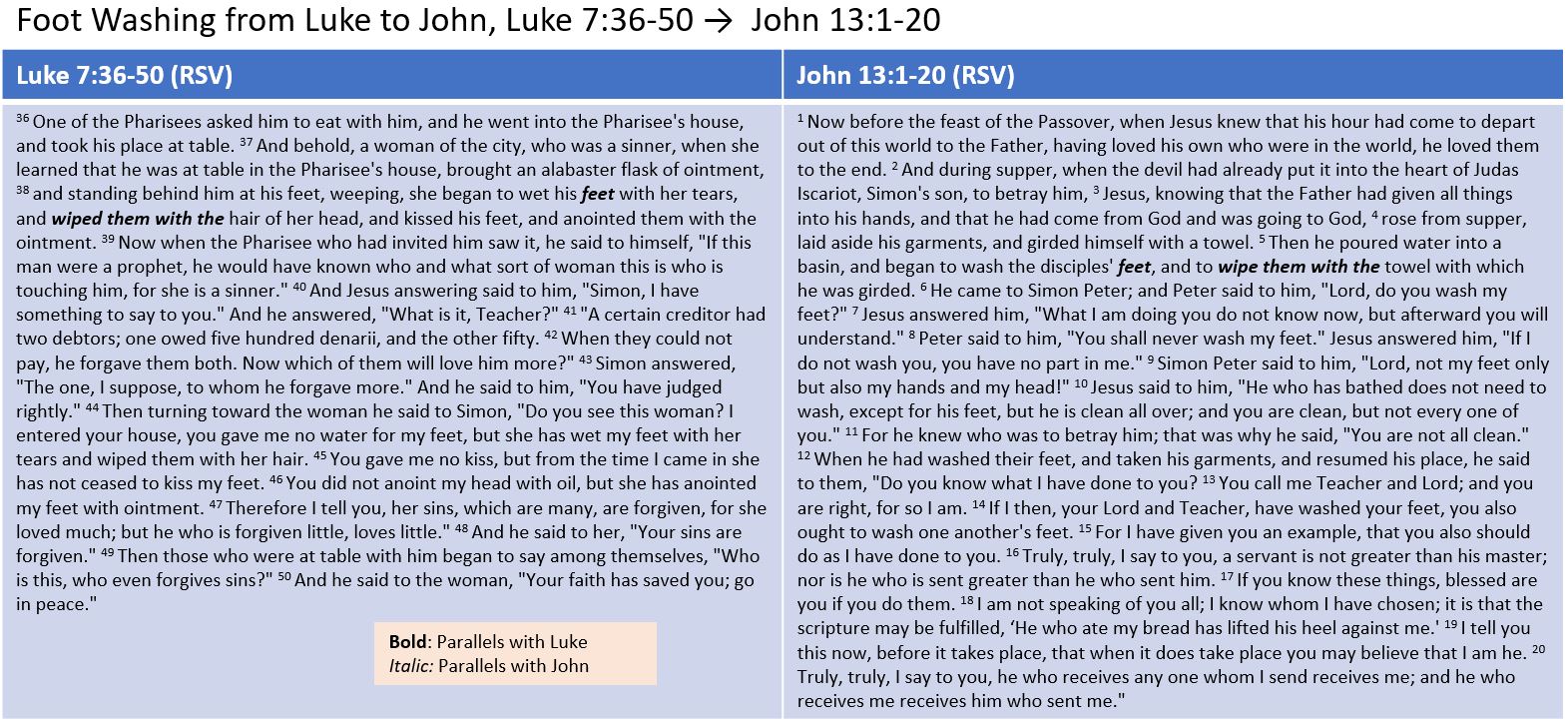

4. Foot Washing from Luke to John, Luke 7:36-50 → John 13:1-20

In Keith L. Yoder’s article “Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John,” he identifies a number of similarities in structure, themes, and narrative elements between the foot washing episodes in the Gospel of Luke 7:36-50 and the Gospel of John 13:1-20.

The strongest evidence for a literary dependence by John on Luke, according to Yoder’s article, is the striking structural and thematic similarities between the foot washing episode in John 13:1-20 and the anointing of Jesus’ feet by the sinful woman in Luke 7:36-50. These similarities suggest that John may have been influenced by Luke’s account when composing his own narrative.

Yoder highlights a number of similarities between the two accounts:

- Both episodes are set in the context of a meal, with Jesus as the central figure.

- Both involve a humble act of service (anointing in Luke, foot washing in John).

- Both accounts emphasize physical touch and the use of a cloth or hair to wipe Jesus’ feet.

- Both stories challenge social norms and expectations.

- Both accounts evoke controversy and criticism from those present.

- Both episodes serve as teaching moments for Jesus.

- The themes of forgiveness and love are central to both stories.

- Both accounts contain an element of imitation, as Jesus encourages his followers to replicate the humble acts they have witnessed.

Structural similarities refer to the shared narrative framework, arrangement of events, and overall organization of the two episodes in question: the anointing of Jesus’ feet by the sinful woman in Luke 7:36-50 and the foot washing in John 13:1-20. These similarities point to the possibility that John’s account of the foot washing may have been influenced by Luke’s account of the anointing of Jesus’ feet, suggesting a process of mimesis or imitation.

The author of John deliberately and adeptly mirrored the written form of Luke’s Sinful Woman narrative. A clear literary link is evident, as the influence of oral tradition falls short of explaining the precise structural and narrative similarities shared by the two stories. The mimetic nature of this connection is demonstrated by the abundant density, sequence, and uniqueness of the parallel features. Additionally, the direction of influence from Luke to John is suggested by consistent indicators in the textual evidence, further corroborated by the significant new understanding gleaned from John’s text. The only plausible conclusion is that John utilized Luke 7:35-50 as the narrative template for his foot washing story while also incorporating select elements from the Luke text into other contexts. It is evident that John replicates the storyline, structures, and transitions of Luke’s narrative but seldom imitates the exact wording. John embodies the archetype of an ideal imitator, capable of delving beneath the superficial verbal aspects of his source to grasp its essence and meaning with a profound understanding of “character and plot.” Consequently, determining the literary relationship between John and another text should involve considering these broader compositional components, rather than relying solely on the existence or absence of verbal parallels.

5. Mary-Marta + Lazarus Stories, Luke 10:38-40, Luke 16:19-31 → John 11:1-45, John 12:1-3

Keith Yoder’s study, “From Luke to John: Lazarus, Mary, and Martha in the Fourth Gospel,” investigates the literary connections between John’s raising of Lazarus and anointing of Jesus texts and Luke’s Lazarus and Mary/Martha texts. Yoder’s analysis reveals a well-organized array of parallels between the Luke and John texts, providing strong evidence of inter-textual influence. He further asserts that this relationship is literary in nature, and that the dependence flows from Luke to John. Yoder provides a summary table with the information below:

| Element | Luke | Order | John |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. “Village” | Luke 10:38 | √ | John 11:1 (30) |

| 2. “Mary, Martha, sister” | Luke 10:39 | √ | John 11:1 (5) 12:2-3 |

| 3. Mary “sitting” | Luke 10:39 | John 11:20 | |

| 4. Mary “at the feet” | Luke 10:39 | John 11:32 | |

| 5. Jesus is “Lord” | Luke 10:39 (40,41) | √ | John 11:2 |

| 6. Martha “serving” | Luke 10:40 | √ | John 12:2 |

| 7. Martha speaks first | Luke 10:40 | √ | John 11:21 |

| 8. Mary silent/shadow | -All- | NA | John 11:32 |

| 9. Incipit “a certain” (10:38,38) | Luke 16:19,20 | √√ | John 11:1 |

| 10. “Lazarus” | Luke 16:20 | √ | John 11:1, John 12:1 |

| 11. Lazarus “died” | Luke 16:22 | √ | John 11:14 (21,32) |

| 12. Lazarus silent/passive | -All- | NA | -All- |

| 13. “lifted up his eyes” | Luke 16:23 | √ | John 11:41 |

| 14. “and said, ‘Father’” | Luke 16:24 | √ | John 11:41 |

| 15. “five brothers” | Luke 16:28 | √ | -ALL- |

| 16. Petition to raise/send back Lazarus | Luke 16:28,30 | √ | John 11:41-43 |

| 17. Petition denied/granted | Luke 16:29,31 | √ | John 11:41,42 |

| 18. Resulting disbelief/belief | Luke 16:31 | √ | John 11:45 |

Keith Yoder further argues in his paper titled “One and the Same? Lazarus in Luke and John” that the Lazarus mentioned in Luke 16 and John 11-12 are largely the same person. In terms of the evidence, there is agreement that John’s Lazarus bears obvious similarities with Luke’s poor beggar, including their shared name, which is distinctive in the New Testament, their deaths, and their involvement in a contemplated or actual resurrection. These and other less apparent similarities align in a well-organized arrangement of direct or inverse linguistic and thematic connections.

Although the ordered arrangement of similarities provides prima facie evidence of allusion to Luke’s Lazarus, there are additional deeply embedded connections that strengthen the case. For example, in Luke’s story, the Rich Man in hell fire asked Abraham to send Lazarus back from the dead to warn his “five brothers” (Luke 16:28). Interestingly, in John 11:1-44, there are exactly five uses of the word “brother” (ἀδελφός) in 11:2, 19, 21, 23, and 32, which is not a coincidence. This is confirmed by the presence of five interwoven uses of the cognate “sister” (ἀδελφή) in 11:2, 3, 5, 28, and 39. The connection to Luke is further reinforced when we consider that John’s use of these two sets of five “brothers” and “sisters” is comparable to Luke’s use of a series of verbal doublets in the Mary and Martha story (Luke 10:38-42) that contrast the opposing reactions of the two sisters to Jesus. John’s use of two matching quintets is simply an adaptation of Luke’s device, featuring the same two women as sisters of Lazarus.

There may be an argument that while the resurrection and the five brothers could have originated from the ending of Luke’s parable (16:29-31), John “shows no knowledge of the main section of the parable.” However, upon closer examination, it becomes clear that John’s characterization of Lazarus is a well-balanced reflection of Luke’s beggar, especially in the main section. Both men are nearly entirely passive. Neither of them speaks, and they are acted upon but never act. Each of them suffers, one from sores (Luke 16:20,21) and the other from sickness (John 11:1-4, 6), and both ultimately die (Luke 16:22, John 11:14). While Luke’s Lazarus was thrown (Luke 16:20) at the Rich Man’s gate and carried (Luke 16:22) to Abraham’s bosom upon death, John’s Lazarus was laid (John 11:34) in a tomb.

It has been argued that a significant difference between the two Lazaruses in the main section of Luke’s parable, which is that John’s story lacks a character functioning as the antithesis to Lazarus. However, the missing antithesis is found in John’s Anointing, where Judas Iscariot is deliberately cast as Lazarus’ opposite, following the same pattern as Luke’s Rich Man. The love connection between Lazarus and the Beloved Disciple, and their joint contrast against Judas, have been previously noted. Lazarus is the first to appear in 12:1-8, just after Jesus opens the paragraph, while Judas is the last to appear before Jesus closes it. At least five significant features are shared in common by Luke’s Rich Man and John’s Judas:

- Both characters have speaking roles and serve as counter-characters to the mute Lazarus.

- Both voice objections to a state of affairs that have been brought about by God or Jesus.

- Both of their objections are negated by divine authority.

- Both characters are portrayed as “men with the money” in their respective stories.

- Both are implicitly depicted as “thieving from the poor.”

6. The Holy Spirit as a Teacher, Luke 12:12 → John 14:26

In both Luke 12:12 and John 14:26, the Holy Spirit is mentioned in the context of teaching and guidance, which is not found in the corresponding passages in Mark or Matthew. Here are the verses for comparison:

Luke 12:12 (RSV)

“for the Holy Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say.”

John 14:26 (RSV)

“But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you.”

In both Luke and John, the Holy Spirit is portrayed as a source of guidance and instruction for believers. The Holy Spirit will teach them what they ought to say (Luke) and bring to their remembrance all of Jesus’ teachings (John). This emphasis on the Holy Spirit’s role in teaching is not found in a similar manner in the parallel passages of Mark and Matthew.

7. Hate, Even Your Own Life, Luke 14:25 → John 12:25

John 12:25, “Whoever loves his life loses it, and whoever hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life,” shows knowledge of Luke 14:25 “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brother as sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple.”

Luke 14:26 (RSV)

“If any one comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple.”

John 12:25 (RSV)

“He who loves his life loses it, and he who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life.”

The use of the word “hate” in reference to one’s own life is not common in the New Testament. The only instances are found in Luke 14:26 and John 12:25. There is no other direct use of “hate” in reference to one’s own life in the New Testament. These specific teachings are not found in the same way in the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of Matthew. While both Mark and Matthew have passages discussing the cost of discipleship and the need to prioritize following Jesus (e.g., Mark 8:34-38, Matthew 10:37-39), they do not use the same language or phrasing found in Luke 14:26 and John 12:25.In both verses, there is an emphasis on the need to “hate” or not love one’s life in this world in order to truly follow Jesus.

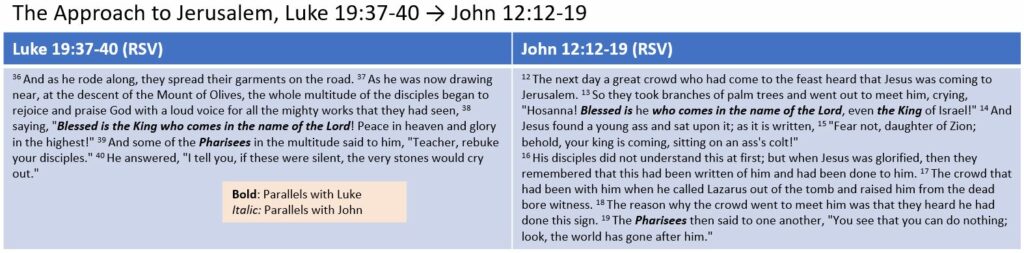

8. The Approach to Jerusalem, Luke 19:37-40 → John 12:12-19

The stories of Jesus’ approach to Jerusalem in Luke and John share common elements that are absent in Mark and Matthew’s accounts. These are the common elements in the Lucan and Johannine accounts of Jesus’ approach to Jerusalem:

- The connection of acclamation to Jesus’ miracle-working activity. In Luke’s account (Luke 19:37), Jesus is acclaimed by his disciples because of the miracles they have witnessed him perform, while in John’s account (John 12:17), the crowd acclaims Jesus because of his raising of Lazarus.

- The use of the words of acclamation in both gospels that match in the Greek.

- The negative reaction of the Pharisees to the acclamation (Luke 19:39 and John 12:19)

9. Jesus staying on the Mount of Olives, Luke 21:37-38 → John 8:1-2

In reference to the Revised Standard Version (RSV) of the Bible, let’s examine Luke 21:37-38 and John 8:1-2:

Luke 21:37-38 (RSV)

“And every day he was teaching in the temple, but at night he went out and lodged on the mount called Olivet. And early in the morning all the people came to him in the temple to hear him.”

John 8:1-2 (RSV)

“But Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. Early in the morning he came again to the temple; all the people came to him, and he sat down and taught them.”

The literary relationship between Luke 21:37-38 and John 8:1-2 lies in their descriptions of Jesus’ daily routine during his time in Jerusalem. In both passages, we see Jesus spending his days teaching in the temple and his nights on the Mount of Olives (or Olivet). Additionally, both accounts mention that the people came to the temple early in the morning to hear Jesus teach.

While both Mark and Matthew mention Jesus teaching in the temple, they do not provide the same details about Jesus’ daily routine of spending nights on the Mount of Olives and people coming to him early in the morning to hear his teachings, as found in Luke 21:37-38 and John 8:1-2.

10. Woman Caught in Adultery, Luke 21:37-38 → John 7:53-8:11

Some scholars have suggested that the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53-8:11) originates from Luke. The style and vocabulary of the story in John are quite different from the rest of the Gospel, and the story is missing from the earliest and best manuscripts of John. The story is found in some manuscripts of Luke’s Gospel (f13 manuscripts including 13, 69, 124, 346), giving some credence that perhaps the story better fits with or originated from Luke. This opens the possibility that the story was possibly known to the author of John’s Gospel through Luke’s Gospel and was inserted into John at a later time. The reason we don’t see the story in most manuscripts of Luke is likely for the same reason we don’t see it in early manuscripts of John. The reason being the story was controversial and likely removed at an early period of increased strictness in the early Church. The most plausible explanation of the delay in the acceptance of this story is likely the ease with which Jesus forgave the adulteress, being hard to reconcile with the stern penitential discipline that became in vogue in the early Church.

Seven Lukanisms are observed in the Pericope Adulterae as follows:

- John 8:2 “at day break” (Orthrou) occurs elsewhere in the NT only in Luke and Acts. Luke 21:38 says that early in the morning all the people came to the temple precincts to hear him.

- John 8:2, Luke shows a preference for the verb παραγίνομαι (to arrive) (8:2), which appears 28 times in Luke-Acts, including eight occurrences in the Third Gospel. This is in contrast to Matthew, where it appears only three times, and Mark and John, where it appears only once each. The sole other instance of this verb being used with εἰς and an accusative of place is found in Acts 9:26.

- John 8:2, The expression πᾶς ὁ λαός (all the people) is predominantly found in Luke’s writings (15 instances in Luke-Acts), while appearing only once in Matthew, and not at all in Mark or John. The word λαός (people/crowd) is a particular favorite of Luke’s (appearing 84 times in Luke-Acts out of 142 NT uses), compared to its usage in Matthew (14 times), Mark and John (2 times each).

- John 8:2, The portrayal of an individual teaching while seated (καθίσας ἐδίδασκεν, 8:2) is largely a distinctive feature of Luke’s writing. The combination of the verbs καθίζω and διδάσκω occurs only twice more in the same verse in Luke’s works (Luke 5:3 and Acts 18:11).

- John 8:6 “so that they could have something to accuse him of” is almost the same Greek as found in Luke 6:7. The entire phrase ἵνα ἔχωσιν κατηγορεῖν αὐτοῦ closely parallels Luke 6:7, which reads ἵνα εὕρωσιν κατηγορεῖν αὐτοῦ. The present active infinitive κατηγορεῖν (8:6) is used exclusively in Luke-Acts (Luke 6:7; 23:2; Acts 24:2; Acts 24:19; Acts 28:19).

- John 8:11, The expression ἀπὸ τοῦ νῦν (from now on) is found only in Luke’s writing (Luke 1:48, Luke 5:10, Luke 12:52, Luke 22:18, Luke 22:69).

- The postpositive δέ is repeated throughout the Pericope Adulterae. Δέ is Luke’s favored conjunction.

Despite the scarcity of evidence supporting other alleged similarities with the other Gospels, the seven distinctive Lukan traits outlined above are uniquely Lukan and align precisely with other instances in the Third Gospel. It is implausible to suggest that a scribe could have so accurately replicated Luke’s style and subsequently inserted the pericope into John’s Gospel.

Raymond Brown comments:

In general, the style is not Johannine either in vocabulary or grammar. Stylistically, the story is more Lucan than Johannine. Nor is the manuscript evidence unanimous in associating the story with John. One important group of witnesses places the story after Luke 21:38, a localization which would be far more appropriate than the present position of the story in John, where it breaks up the sequence of the discourses at Tabernacles. (Raymond. E. Brown, The Gospel According to John (I-XII), The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries, (1995) p. 336)

Another significant observation is that John 8:1 says, “Jesus went out of Mount of Olives.” Luke 21:37 says that during the last days of his life, Jesus lodged on the Mount of Olives. The indication here as that the original disposition of the story is probably after Luke 21:37-38.

References:

- Joseph A Fitzmyer, The Gospel according to Luke (X-XXIV) : introduction, translation, and notes, The Anchor Bible Commentary (1981), p. 1358

- Raymond. E. Brown, The Gospel According to John (I-XII), The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries, (1995) pp. 332-338

- H. J. Cadbury, “A Possible Case of Lukan Authorship” (John 7:53-8:11),” HTR 10 (1917) 237-244

- F. A Shilling, “The Story of Jesus and the Adulteress,” ATR 37 (1955), 91-106

- Kyle R. Hughes, “The Lukan Special Material and the Tradition History of the Pericope Adulterae,” Novum Testamentum 55 (2013) 232-251

11. Satan and Judas, Luke 22:3 →John 13:2, 27

Let’s examine Luke 22:3 and John 13:2, 27:

Luke 22:3 (RSV)

“Then Satan entered into Judas called Iscariot, who was of the number of the twelve.”

John 13:2 (RSV)

“And during supper, when the devil had already put it into the heart of Judas Iscariot, Simon’s son, to betray him,”

John 13:27 (RSV)

“Then after the morsel, Satan entered into him. Jesus said to him, ‘What you are going to do, do quickly.’”

The literary relationship between Luke 22:3 and John 13:2, 27 lies in their descriptions of Satan’s influence on Judas Iscariot, which led to his betrayal of Jesus. In both accounts, Satan is portrayed as actively participating in Judas’ actions. Luke 22:3 states that Satan entered into Judas, while John 13:2 mentions the devil putting the idea to betray Jesus into Judas’ heart, and John 13:27 reiterates that Satan entered into him.

In Mark and Matthew, the betrayal of Jesus by Judas is also mentioned, but the specific role of Satan in influencing Judas is not explicitly emphasized:

Mark 14:10-11 (RSV)

“Then Judas Iscariot, who was one of the twelve, went to the chief priests in order to betray him to them. And when they heard it, they were glad, and promised to give him money. And he sought an opportunity to betray him.”

Matthew 26:14-16 (RSV)

“Then one of the twelve, who was called Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests and said, ‘What will you give me if I deliver him to you?’ And they paid him thirty pieces of silver. And from that moment he sought an opportunity to betray him.”

The literary relationship between Luke 22:3 and John 13:2, 27 involves the specific emphasis on Satan’s role in influencing Judas to betray Jesus, which is not shared in the same way with the accounts in Mark and Matthew.

Moreover, John’s dependence on Luke is evidenced by the interesting phenomenon with Luke 22:3, John 13:2, and John 13:27. John presents two statements parallel to a statement in Luke (although John 13:2 is not as close as the other one). There is no doubt that John derived the John 13:27 statement from Luke. It can be concluded that the tradition that Judas’ betrayal was inspired by the devil entered the gospel tradition through the activity of Luke, and was then taken over and further developed by John.

12. The Last Supper, Luke 22:14-38 → John 13-17

The similarities between Luke 22:14-38 and John 13-17 that are not shared by Mark and Matthew include:

-

John’s Gospel includes a lengthy discourse from Jesus to his disciples during the Last Supper, which covers various topics, including instructions for his disciples, prayers to God, and promises of the coming Holy Spirit. Luke’s Gospel includes some teachings and instructions from Jesus during the Last Supper, but they are not as lengthy or comprehensive as those found in John’s Gospel. Mark and Matthew do not include any significant discourse or teachings from Jesus during the Last Supper.

-

In John’s Gospel, Jesus promises the coming of the Holy Spirit, who will be the Advocate and guide for his disciples. This promise is not mentioned in Mark or Matthew’s accounts of the Last Supper. While the promise of the Holy Spirit is not explicitly mentioned in Luke’s account of the Last Supper, it is alluded to in other parts of Luke’s Gospel.

-

John’s Gospel includes a prayer from Jesus for his disciples, in which he asks God to protect them and keep them unified. This prayer is not mentioned in Mark or Matthew’s accounts of the Last Supper. While a prayer from Jesus for his disciples is not explicitly mentioned in Luke’s account of the Last Supper, it is alluded to in other parts of Luke’s Gospel.

Overall, the accounts of the Last Supper in Luke 22:14-38 and John 13-17 share several unique details that are not found in the parallel passages in Mark and Matthew, including Jesus’ lengthy discourse, the promise of the coming Holy Spirit, and Jesus’ prayer for his disciples. These unique features in Luke and John’s Gospels provide additional insights into the events of the Last Supper and Jesus’ teachings to his disciples during this time.

13. From the Last Supper to the Arrest, Luke 22:39-53 → John 18:1-12

In the accounts of Jesus’ actions from the end of the Last Supper until his arrest, Luke and John share several common points:

- The disciples are explicitly mentioned as accompanying Jesus when he leaves the meal (Luke 22:39, John 18:1).

- Jesus’ destination is not named Gethsemane.

- The location where Jesus is arrested is mentioned as a place he frequently visited (Luke 22:39, John 18:12).

- Jesus is arrested at the end of the scene when his attackers approach him (Luke 22:54, John 18:12); the disciples’ use of force is an attempt to prevent his arrest, not to free him, as in Matthew and Mark.

- The role of Judas’ kiss is downplayed compared to Matthew and Mark.

- The high priest’s servant’s right ear is cut off.

- The disciples do not flee.

The information in Luke 22:39 that Jesus went to the Mount of Olives as was his custom comes from, and agrees with, that in Luke 21:37, which clearly originates from Luke’s pen and represents his effort to create coherence in the account of Jesus’ stay in Jerusalem. Similarly, the notice that it was the high priest’s servant’s right ear that was cut off comes from the evangelist, as a comparison of Luke 6:6 with Mark 3:1 makes clear.

John’s reliance on Luke here should not be considered passive, as the differences between the two accounts make evident. John utilized Luke’s version because it offered a scene more acceptable to him than Mark’s, suggesting a framework for the portrayal he wanted to include in his own gospel. However, John didn’t hesitate to deviate from Luke when he felt it didn’t align with the correct presentation.

The author of John followed and enhanced the emphasis he discovered in Luke’s account. As such, it is inaccurate to view the agreements between Luke and John as merely isolated similarities within different contexts. The most significant commonality between the two is their emphasis on Jesus’ dominant position.

John likely depended on Luke for the positive similarities between their accounts, with the possible exception of the mention of the disciples at the end of the Last Supper. Furthermore, their shared content does not stem from a source exclusive to Luke (which could potentially be historically accurate) but rather from his own understanding of the events surrounding Jesus’ arrest.

14. Jesus’ Appearance before the Jewish Authorities, Luke 22:53-71 → John 18:13-28

Luke’s and John’s descriptions of Jesus’ appearance before the Jewish authorities align in that neither portrays a formal trial with witnesses and a verdict, unlike Mark and Matthew. Additionally, there are indications that Luke concurs with John in considering Annas as the primary Jewish dignitary at the hearing.

The Johannine source with Annas as the high priest finds a counterpart in Luke’s gospel. Both evangelists also agree that Jesus’ examination by the Jews did not constitute a formal trial. John drew on the non-Marcan account of the scene in addition to Mark in their descriptions of Jesus’ examination by the Jewish authorities. The difficulty of producing a problematic account based solely on synoptic sources makes it highly unlikely that John could have started from scratch and created such a passage.

15. The trial before Pilate, Luke 23:1-25 →John 18:29-19:6

The accounts of Jesus’ trial before Pilate in the books of Luke and John share several similarities:

- Pilate declares three times that Jesus is innocent, with John’s declarations being unqualified (Luke 18:38, Luke 19:4,19:6), while in Luke, Pilate declares Jesus absolutely innocent once and innocent of any capital crime twice (Luke 23:4,13,22).

- The first declaration is accompanied by a question from Pilate and Jesus’ answer (Luke 23:3, John 18:33, 37).

- It is explicitly stated that Pilate tries to release Jesus (Luke 22:16, 20, 22; John 19:12).

- The scourging of Jesus is mentioned in the context of his release, not his conviction (Luke 23:16, 22; John 19:1).

- Pilate mentions a group of Jews, beyond just the Sanhedrin, who handed Jesus over to him (Luke 23:13, John 18:35).

- Jesus is charged with claiming to be a king (Luke 23.2, John 19:12).

- In both accounts, Barnabas is mentioned only after the Jews demand his release (Luke 23:18, John 18:40).

- The same word is used by the crowd in crying for Jesus’ destruction (Luke 23:18, John 19:15)

-

“Crucify” is repeated twice by the hostile crowd (Luke. 23:21, John 19:6)

The most notable agreement is the three declarations made by Pilate. This statement was sourced from Luke, as evidenced by its content and form. The content of the three-fold statement is in excellent accord with Luke’s theology, according to which the Jews alone were responsible for Jesus’ death. The connection between the three-fold statement and the Herod scene in Luke’s gospel further supports the idea that it originated with the Luke, rather than another source.

As for John’s gospel, it is likely that he knew Luke’s gospel and was impressed enough with the three-fold statement to incorporate it into his own gospel. The marked similarity in vocabulary and form between John’s statements and Luke’s first, unqualified statement of innocence provides evidence for this argument.

In John’s gospel, the belief in Jesus’ innocence on the part of Pilate is even clearer than in Luke’s account. This is due to the unqualified form of all Pilate’s statements in John and the inclusion of two dialogues between Jesus and Pilate which explain why Pilate knew that Jesus was innocent. These dialogues represent John’s development of the three-fold Pilate statement he took over from Luke, particularly in John 18:33-38, which expands on Luke 23:3. John not only provides a commentary on what he found in Luke, but also transforms its content. It is evident that where there are similarities, they are not due to a shared written or oral source, but rather because John has followed Luke.

16. Jesus’ Crucifixion, Death and Burial, Luke 23:25-56 → John 19:17-42

Luke and John share several common points in their accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, death, and burial.

- Both mention that two other men were crucified with Jesus immediately after his own crucifixion (Luke 23:33, John 19:18).

- They use the same Greek word to describe the women who watch Jesus on the cross. (Luke 23:49, John 19:25).

- Both Luke and John note that the tomb where Jesus was buried had never been used before (Luke 23:53, John 19:41), followed by the statement that it was the day of Preparation for the Sabbath.

In addition to these agreements, there are several negative agreements between the two gospels. Neither Luke nor John records the giving of wine mixed with myrrh to Jesus, the mocking reference to Jesus’ alleged statement that he would destroy the temple, Jesus’ cry of “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”, or the sealing of the tomb with a stone.

Considering all the agreements between the accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, death, and burial in Luke and John, it is clear that the non-coincidental agreements are due to John incorporating elements from Luke’s account.

17. Resurrection and Post-Resurrection Narratives, Luke 24 → John 20

The accounts of the finding of the empty tomb and the appearance of the risen Christ in Luke and John share several common elements.

- Mary Magdalene (and in Luke, the women accompanying her) seeks out the tomb before sunrise.

- Two angels appear at the tomb to Mary Magdalene (and the women with her in Luke).

- Several disciples go to the grave on the basis of what Mary Magdalene (in Luke, she and the other women) tells them about its being empty, and find that what they have been told is true.

- Late on Easter Sunday, Jesus appears to a group of disciples in Jerusalem, demonstrating his corporeality by showing them his wounds. In connection with both appearances, the disciples’ joy is mentioned, and Jesus speaks to them of the forgiveness of sins and the Spirit, and of the role of his hearers – indeed, in both cases, his words constitute his commission to his Church.

- Both Luke and John record an appearance of Christ to Peter.

Regarding the resurrection appearance in John 20:19-23, it is clear that John knew Luke’s gospel, as the similarity to Luke 24:36-43 is too great to be accidental. Luke is, in fact, John’s source for this account. John derived from Luke, Jesus’ sudden appearance “in the midst” of the disciples, the timing of the appearance on Sunday afternoon, its location in Jerusalem, and the emphasis on the physical nature of Jesus’ body. However, the original nature of the appearance as recounted by Luke, in which the disciples’ unbelief is overcome by proofs of increasing power, is no longer clear in John’s recasting of the account.

18. Examining of Jesus’ Wounds, Luke 24:37-39 → John 20:24-28

The recognition of Jesus by his wounds by the disciples is unique to Luke 24:37-39 in the Synoptic Gospels. The physicality of Jesus’ resurrection was a subject of debate in the early Church, including in the Johannine epistles. Some suggest that the second appearance of Jesus to the disciples in John 20:24-28 was added later by an editor. However, the parallel between the two accounts is striking, particularly the emphasis on Jesus inviting the disciples to observe his hands, which was previously omitted. This suggests that John was familiar with Luke’s Gospel, as the final editor chose to retain this detail consistent with Luke’s account.

Shared Themes and Motifs that Suggest a Literary Relationship

Additionally, there are several shared themes and motifs between the Gospel of John and the Gospel of Luke, which have led some scholars to suggest a literary relationship between the two gospels. Here are a few examples:

The Holy Spirit:

Both John and Luke place a strong emphasis on the role of the Holy Spirit in the life of Jesus and his followers. In Luke’s gospel, the Holy Spirit is prominently mentioned in the birth and baptism narratives, and in Acts it plays a central role in the formation and mission of the early church. In John’s gospel, the Holy Spirit is associated with Jesus’ baptism and is promised as a helper and guide for his disciples after his departure.

The Journey to Jerusalem:

Both gospels place a significant emphasis on Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem, which culminates in his death and resurrection. In Luke’s gospel, this journey is a major part of the narrative, with Jesus repeatedly predicting his impending death and resurrection. In John’s gospel, the journey to Jerusalem is also a key theme, with Jesus using it as an opportunity to teach his disciples about his identity and mission.

Emphasis on prayer:

Both John and Luke portray Jesus as someone who frequently prays and teaches his disciples about prayer. Luke includes several unique parables on prayer, such as the parable of the persistent widow, while John includes Jesus’ prayer for his disciples in John 17.

Focus on marginalized groups:

Both John and Luke emphasize the importance of caring for marginalized groups, such as the poor, the sick, and the outcasts of society. For example, Luke includes several healing stories involving people who are outcasts in their society, while John includes the story of the woman at the well, who is a Samaritan and therefore an outsider in Jewish society. Both gospels record that Jesus went to Samaria and encountered a response of faith there. Luke describes how Jesus and his disciples were rejected by the Samaritan villagers, and then he heals ten men of leprosy, one of whom is a Samaritan. John’s gospel records the well-known encounter between Jesus and the Samaritan woman at the well.

Women Disciples:

Both John and Luke highlight the prominent role of women in the Jesus movement. In Luke’s gospel, women are portrayed as faithful followers of Jesus and witnesses to his resurrection. In John’s gospel, women play a similar role, with Mary Magdalene being the first witness to the resurrected Jesus.

Emphasis on love:

Both John and Luke emphasize the importance of love in the life of Jesus and his followers. For example, Luke includes the command to “love your neighbor as yourself” and the parable of the prodigal son, while John includes the command to “love one another as I have loved you” and the story of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet as a symbol of humble service and love.

Conclusion

The author of the Gospel of John was familiar with the Gospel of Luke and used it as a source. This is substantiated by numerous instances where the Fourth Gospel alludes to or is dependent on Luke’s Gospel.

Scholars have noted numerous parallels between John and Luke, such as the use of similar language and the arrangement of certain stories. These similarities are too striking to be coincidental, and suggest that the author of John’s Gospel was familiar with Luke’s Gospel and used it as a source.

Overall, the argument for John’s familiarity with Luke’s Gospel is demonstrated by a close literary analysis and a careful comparison of the two texts.

*Editorial Note

The research and composition of this article were assisted by GPT-3, OpenAI’s large-scale language-generation model. Upon generating some text in this article, the language was reviewed and edited to the satisfaction of the author, who takes ultimate responsibility for the content of this publication.